Note: The following biography was obtained from the Sid Sackson Collection at the Brian-Sutton Smith Library and Archives of Play located within the Strong National Museum of Play in Rochester, New York.

| |

Sid Sackson was born in Chicago, Illinois, on February 4, 1920. He was fascinated by games from a very early age, with his mother buying him a new game every week.

As a small child, he worked on improving the games he received. His first effort involved modifying his Uncle Wiggily game until it became a war game with soldiers and cannon. He found the Lotto game dull, so he turned it into a solitaire game of historical empires.

During the 1930s Sackson’s family moved from city to city (including Gary, Indiana, and Philadelphia) as his father searched for employment. The young boy spent many hours creating, modifying, and playing games alone or with his father. Young Sid also developed an interest in ballroom dancing and served as the editor of his high school newspaper.

In 1937, he entered City College of New York, from which he graduated magna cum laude with a Bachelor of Science degree in civil engineering. He became a professionally licensed civil engineer . Among other projects, he worked on the battleship Missouri, the aircraft carrier Yorktown, the Verrazano-Narrows Bridge, and the World Trade Center.

He established his residence in the Bronx with his wife Bernice, whom he married in 1941, and eventually their son and daughter. The Sacksons did jigsaw puzzles together but quickly switched to board games. They developed a circle of friends who were also game fans, and many evenings were spent playing games.

As Sackson developed his passion for creating games, his family and friends often play-tested his efforts. His first published game was Poke, a poker variation that he submitted to Esquire in 1946. A two-handed version of bridge, called Slam, was published in a syndicated bridge column in 1951. Although he invented scores of games, he did not sell any during this time.

In 1958, Sackson met a game inventor who was demonstrating his products in Gimbel’s Department Store. The inventor introduced Sackson to his agent, who agreed to try to place some of Sackson’s games with manufacturers. Milton Bradley finally agreed to buy Sackson’s game High Spirits in 1962. To Sackson’s disappointment, the firm changed the adult game into a mediocre children’s game, High Spirits with Calvin and the Colonel, named after a television program.

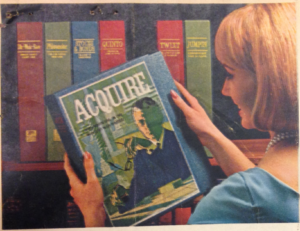

However, during that time he had modified his early solitaire game based on Lotto into a multi-player game that he called Acquire. He sold that game to 3M Company, which successfully published it and five other Sackson games in the 1960s and early 1970s. Sackson considered Acquire one of his best and most successful games.

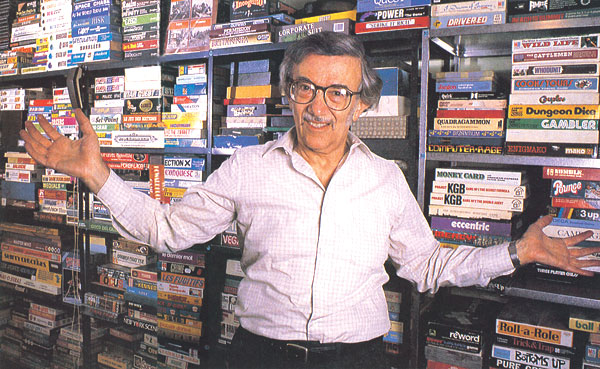

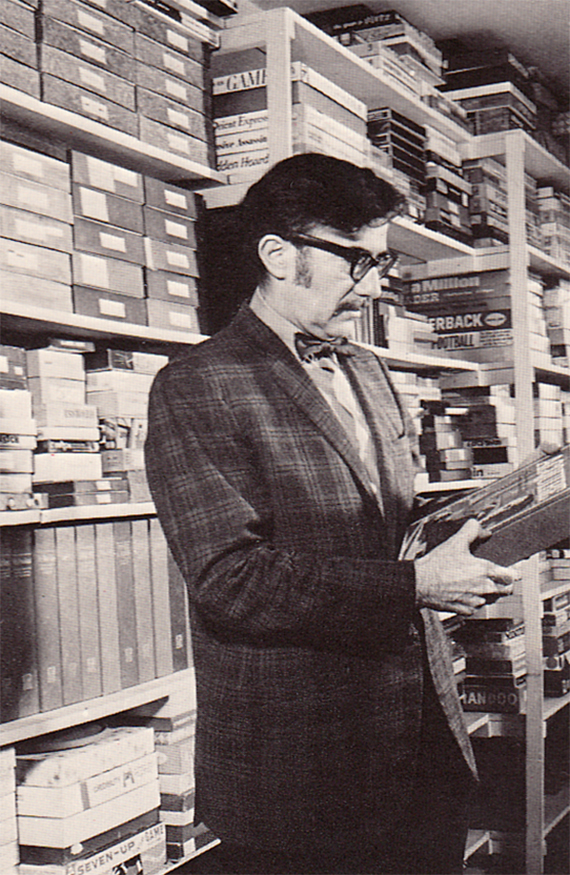

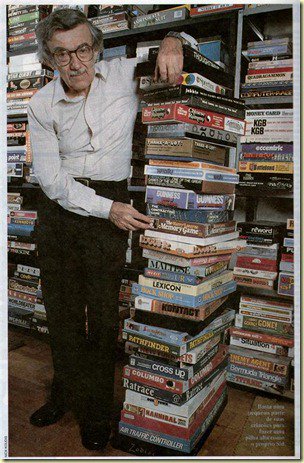

During the 1960s Sackson and his wife traveled to Europe several times, meeting game enthusiasts and purchasing items for Sackson’s growing collection of board games and reference works on games. Sackson’s collection of over 15,000 games eventually filled three rooms and the basement of his house, with games stacked from floor to ceiling. File cabinets contained reproductions and detailed descriptions of rules for thousands of games. He also kept daily work dairies, many meticulously indexed, of all his game-related activities, contacts, and ideas.

Sackson wrote A Gamut of Games, a collection of card, board, and party games that was published by Random House in 1969. The book contained games developed by Sackson and several of his friends, as well as a few classics. It also included an appendix of short reviews of “games in print.” The book became popular among game enthusiasts, was reprinted in several editions over the next 15 years, and is considered a classic work.

Patterns, a game of inductive logic that Sackson had created for A Gamut of Games, was featured in Martin Gardner’s November 1969 column in Scientific American and appeared on the issue’s cover. The column attracted considerable interest in the scientific community and garnered wide publicity for Sackson.

By 1970 Sackson was making more money from his games than from his engineering job. His need for flexibility to continue inventing games and writing game reviews for Strategy & Tactics magazine prompted him to quit the engineering field and devote all his time to his passion during the next 25 years. Sackson ultimately created over 500 games; about 50 were marketed. Among his most notable were Acquire, Can’t Stop, Sleuth, Focus (Domination), Bazaar, Metropolis, Monad, Take Five, and Venture.

Foreign editions of his games were published, particularly in Germany where his games found a wide audience in the 1980s and 1990s. His games received several European awards. Some games have been reissued in special editions since his death. Sackson wrote game reviews for Strategy & Tactics, Games magazine, and the Gamers Alliance Report. Many of his games were published in Games issues, while Pantheon published five books of Sackson games and Prentice-Hall published a Sackson book, Playing Cards Around the World.

He corresponded with professional game designers as well as amateurs who developed ideas for games and asked him for advice and critiques. Annual visits to the Toy Fair in New York City were opportunities to meet colleagues and to acquire more games and reference materials for his huge collections.

By the mid-1990s Sackson’s health was declining. His final years were spent in a nursing home, and he died on November 6, 2002. His vast collection of games, which he had always hoped would be purchased whole by a museum, was auctioned off individually and in lots to game fans and collectors in 2002-2003.

Sackson believed the inspiration for designing a game was simple: he just built on something he found interesting. He liked to play games because his brain felt good after a mental workout, and “it’s fun to show how smart you are.” He enjoyed the companionship involved in playing games, which was a key reason he didn’t enjoy computer games: “there is no human face across the table.” Sackson played games to win but didn’t especially care if he won or lost, believing “it’s only important that the game was interesting."

Biographical Sources:

• Eskin, Blake, “Sold Separately,” The New Yorker, January 20, 2003, http://www.newyorker.com/printables/talk/030120ta_talk_eskin (accessed 1/4/2007).

• Gamers Alliance tributes to Sid Sackson, http://www.gamersalliance.com (accessed 3/14/2006).

• Glenn, Stephen, “An Exclusive Interview with Game Master, Sid Sackson,” http://www.webnoir.com/bob/sid/interview.htm (accessed 1/8/2007).

• Miscellaneous manuscript and published biographical/autobiographical material, Sid Sackson Collection, Sub-Series 1-4.2 Articles and Miscellaneous Items by and about Sid Sackson.

• Sackson, Sid, A Gamut of Games, New York: Random House, 1969, p. vi.

• “Sid Sackson,” Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sidney_Sackson (accessed 1/8/2007).

• Whitehill, Bruce, “Sid Sackson: America’s Grand Game Inventor,” Knucklebones, May 2006, pp. 40-41.

• Zetlin, Minda, “The Guru of Games,” originally published in Games Magazine, Feb./Mar. 1987, http://www.webnoir.com/bob/sid/zetlin.htm (accessed 1/8/2007).